Kafr Hassan Dawood

The History of the Site & Site Formation Processes

The geological and geoarchaeological processes at KHD have been studied and mapped by Dr. M. Abdel-Rahman Hamden, Prof. P. Sinclair (University of Uppsala) and Prof. F. A. Hassan. The full report on the topographic mapping, microstratigraphy and geophysical prospection is summarised here and is available in full in the references section. In essence, KHD’s immediate environment is defined by a sequence of five local and Nilotic sedimentary units, overlain by aeolian sand. Their variability shows changing riverine and ecological conditions through time:

(5) Alluvial-Colluvial Unit (newest)

(4) Upper Nile Mud Unit

(3) Upper Sand Unit

(2) Lower Nile Mud Unit

(1) Basal Sand Unit (oldest)

From 500,000 to 150,000 years ago (the Pleistocene) the KHD area was part of a massive river system; the river deposited a vast quantity of largely Equatorial East African sediment that now comprises the Basal Sand Unit (1).

The Late Upper Pleistocene (30,000-12,000 years ago) saw massive river activity caused by a much lower sea level (100m lower than today). This caused severe erosion, slicing river courses deep into older Pleistocene deposits and forming the Wadi Tumilat. Remnants of the BSU were left as a low, wide terrace on both banks of the Wadi, and this is where the site of KHD is located. At the terminal Pleistocene (14-12,000 years ago), enormous Nile floods caused the deposition of extensive riverine sediments that are termed the Lower Nile Mud Unit (2).

The upper aspect of the LMU (2) is eroded and irregular, reflecting an Early Holocene (8-6,000 years ago) drop in sea level that accelerated erosion of the floodplain. Small wadis drained the terraces around KHD, reworking the LNMU and depositing the Upper Sand Unit (3).

Reddish paleosols at the top margin of the USU indicate dry conditions and warm summers, followed by resumption of fluvial erosion triggered by repeated Nile floods. The deposits from this episode are dubbed the Upper Nile Mud Unit (4), comprising 2m of Nile silts and assorted detritus.

The Alluvial-Colluvial Unit (5) was deposited shortly before human activity in the SW part of the site. The unit is diverse, containing both alluvial and colluvial sediments running N-S. The alluvial section contains gravel, sand and silt that filled a channel, and which was then covered by a colluvial layer of white ash and rubble lag gravel, rich in phytoliths. The channel was identified by excavation; it is 10m wide and 1.5m thick and runs for more than 100m across the current site area.

Humans were definitely present at KHD from at least 5,500 years ago (3,500 BC), as evidenced by the Predynastic-Early Dynastic cemetery. By this time the palaeotopography was much as it is at present; Middle Pleistocene sand and channel sand are seen as terraces to the South, while a wide floodplain basin lies to the North (the main Nile branch lies even further to the North). This area would therefore have been marshy and swampy during high floods, while being comparatively dry (and perhaps subject to wadi runoff or colluvial activity) in low floods. Human groups evidently decided to site their cemetery on the sandy terraces, and – to judge from coring – seem to have used the flood basin to site their settlement. Lithological analysis also indicates that they transported silts from the floodplain to the cemetery, as part of their funeral rites.

The site was abandoned during the Early Dynastic Period, and the settlement covered by c. 4m of silt. There are some indications that the area was used for cultivation into the Old Kingdom, comprising calcified root casts, manganese/ochre staining and hearths rich in organic content overlying the graves. The Late Old Kingdom saw drier conditions, interspersed with interludes of floods that transported local materials and artefacts to the flood basin.

The site was unoccupied from the Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom, which saw a gradual decrease in flooding that reached a notable low during Dynasty XX. The area was reoccupied during the Late Period (c. 600BC), perhaps as a result of high Nile floods that forced human groups into the high eastern areas. The settlement was expanded into the Ptolemaic period, then was abandoned and subjected to wind erosion and sediment deflation.

The Location of Kafr Hassan Dawood

Longitude: 31.850000 (31o51’0”E)

Latitude: 30.516666 (30o30’59”N)

Geology and Environment

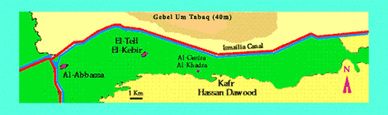

The site is located at the southern edge of the cultivated floodplain of a defunct Nile tributary called the Wadi Tumilat (Fig. 1), in the north-east Delta and close to the Suez Canal. The wadi floor is 5.5-6.5 masl, and is comprised of heavily cultivated Holocene floodplain sediments (towards the North). The South of the site is surrounded by <6m-tall sand dunes extending NW-SE, remnants of the Late Quaternary dune field that covered nearly all of northern Egypt. The Wadi Tumilat originally ran from the apex of the Delta to Lake Timsah (one of the Great Bitter Lakes), which later became a transport route when canals were dug to facilitate water travel from the Nile to the Red Sea. The route was later abandoned. A modern irrigation canal known as Tir’et El-Gebel (or Tir’et El-Sandouq) passes the North of the settlement.

Archaeology of the Area

The area was surveyed in the 1920s (Schott et al in: MDAIK 1932) and again in the 1970/1980s (Holladay & Redmount et al forthcoming). The general consensus of both surveys was that the Wadi was most heavily occupied in the Hyksos period (Second Intermediate Period – Middle Bronze Age) and the Late Period to Graeco-Roman times (Early Iron Age). Multi-period tells are dotted along the Wadi – including Abbasa, Tell Shagafiya, Tell el-Retaba, Tell Maskhuta and Tell al-Ahmar (Redmount in: NARCE 1986: 20) – but show minimal early occupation. This may be a reflection of scanty early settlement, or a reflection of how surface collections always bias in favour of later periods (especially on tell sites).

More recent work has repeatedly demonstrated that the Wadi was in fact occupied from the Palaeolithic period onwards. Although the area is well-sited for Delta-Sinai-Western Asia trade, there is little indication that this occurred at KHD (at least) as few Asiatic objects have been recovered from the cemetery. It may have been a node on the Southern East Delta trade route like sites 31/47/48/53, although evidence is currently lacking. The relative isolation yet large size of KHD is puzzling. However, while comparisons with other Delta cemetery sites such as Minshat Abu Omar and Tell Ibrahim Awad indicate a low ranking for KHD, it was evidently a site of importance within the Wadi Tumilat, although its exact internal ranking is currently uncertain given that no other PD/ED site has so far fully excavated in the region.

Site

The concession covers an area of 91 feddans (95 acres or 38.4 hectares [384,393 m2]), adjacent to the hamlet (Kafr) of Hassan Dawood. The site is 8 km East of At-Tell el-Kebir, 6 km West of El Qasassin El-Kadima (old Qasassin) and c. 40 km West of Ismailia. Kafr Hassan Dawood is located in the Abu Kabir Markez in the Governorate of Ismailia (696/868 Egypt Map, Ismailia Governorate; UTM grid UU87; Alexandria Digital Library Gazette Entry Report: http://fat-albert.alexandria.uscb.edu:8...gaz_report?adl1_num=adlgaz-1-1847314-61). The site is primarily known for its burials, although a habitation area is also known but is as yet unexcavated. The graves were dug into alluvial sands of a low Nile terrace, a few metres above the floodplain. The burials are about 6-7 masl, 1-2 meters below the surface in a layer of sand mixed with silt and fluvial gravel. Directly to the North of the excavations lie two modern Islamic cemeteries, and a disused Coptic cemetery.

FIGURE 1A

FIGURE 1A

FIGURE 1A

Astronaut Photograph of the West Wadi Tumilat (Image courtesy of Earth Sciences and Image Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center, Photo No. ISS006E30451 [http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov]).

FIGURE 1B

FIGURE 1A

FIGURE 1A

Astronaut Photograph of the Kafr Hassan Dawood and the Surrounding Area (Image courtesy of Earth Sciences and Image Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center, Photo No. ISS006E30451 [http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov]).

FIGURE 2A

FIGURE 1A

FIGURE 2A

Astronaut Photograph of the Nile Delta, the Wadi Tumilat can be seen on the right (East), just below the main Delta fan (Image courtesy of Earth Sciences and Image Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center, Photo No. ISS006E30447 [http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov]).

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 2A

Location of Kafr Hassan Dawood in the Wadi Tumilat

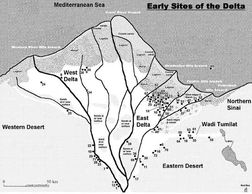

FIGURE 2

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 2

Map of the Nile Delta, c. 3,000 BC showing the settlement patterning of the major Predynastic to Early Dynastic sites (compiled by and copyright [copyright sign] Joris van Wetering, based on initial investigations and analysis of Butzer 2003 and Stanley 2003).

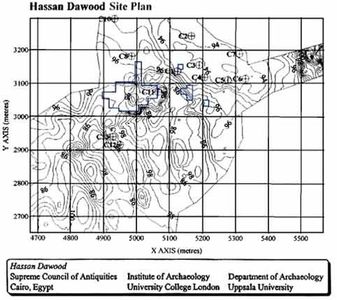

POSITION OF EXCAVATION TRENCHES WITHIN THE KHD GRID

To give comprehensive horizontal and vertical control of the site, a datum and formal site grid were established in Spring 1996. This system will be continuously referenced in all future excavations at KHD. A base-station for the site grid was cemented in at 5000E/3000N; a site datum was established at point and given the arbitrary elevation of 100 metres.

The area showing evidence of cultural activity (ca. 600 x 600 m) was recorded using a total station, taking more than 1400 points; the area was also gridded using wooden stakes with metal tags. The coordinate points were downloaded from the total station into a computer and gridded on a 5 m net using the kriging option of SUFFER. This resulted in a detailed topographic map of the site, and a digital terrain model.

FIGURE 7

FIGURE 7

FIGURE 7

The KHD site grid showing the position of the western and eastern excavation trenches, which are marked out in blue.

FIGURE 8

FIGURE 7

FIGURE 7

The Excavation Unit in the Western Cemetery at KHD.

KHD Excavation History

Local inhabitants of the small hamlet Kafr Hassan Dawood had been aware of archaeological remains on their doorstep long before archaeological work began at the site. The Egyptian Antiquities Authority (Canal Zone) were made aware of the remains in 1977, but nothing was done until 1988 when Mohammed Ilewa el-Moslamy carried out prospection work ahead of a planned land reclamation project. The surveyors reported that their pitting had revealed the remains of a Predynastic to Early Dynastic cemetery.

Full-scale excavations commenced in 1989 under Mohamed Llewa El-Moslamy (Ex-Director General of the district), who mapped in a series of 10x10 metre squares that were cleared of sterile (aeolian) sand by backhoe, then excavated by two teams of 50 workers. Although various unusual or valuable items were removed, the majority of the graves and contents were left in situ and coated in a thick layer of consolidant. Intending to turn the site into an open-air museum, the archaeologists covered part of the site with a plastic and steel ‘greenhouse’ as an attempt to conserve the remains contained within. This had the opposite effect, causing condensation to form and the water level to rise, resulting in a hard salt crust forming on the surface of the graves and many of the objects. Various burials were selected for block-lifting, and were consolidated with nitrocellulose or beeswax before being sheeted with plastic and coated with layers of bitumen and cement.

The excavations were halted for re-evaluation in 1995, by which time the excavators had located 921 graves. However, the excavators’ lack of training had done serious damage to the exposed and unrecorded remains, leading Prof. Fekri Hassan to initiate a programme of research, conservation and training at the site. This was to comprise hands-on training and lectures for inspectors and students, with a particular focus on bioarchaeology. Professor Simon Hillson and Drs Nancy Lovell and Teri Tucker were brought in from the UK, analysing the few skeletons (n=33) that had survived earlier excavations, while also excavating new burials and carrying out training and lectures. The students worked in small groups in 10m squares, and learned the value of a slow, measured approach to skeletal excavation, and also the value in retaining and analysing them rather than leaving them to deteriorate. They were watched over by a large group of physical anthropologists, conservators, recorders and other specialists, guiding their every move.

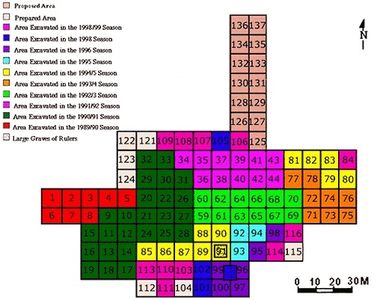

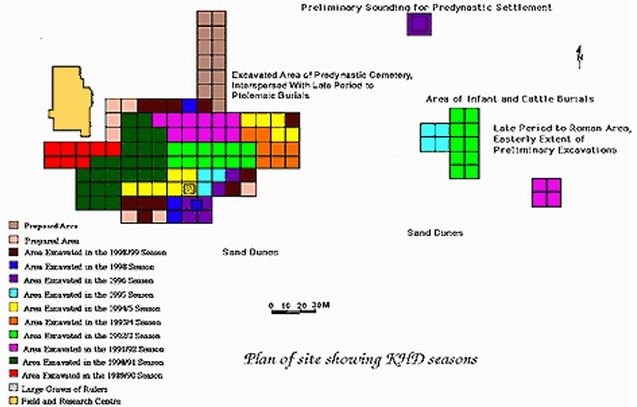

The 1995-1999 seasons resulted in the discovery of 137 Predynastic to Early Dynastic graves, in an excavated area of 117x10m squares that totalled 11,700 square metres. A map of progress in the first five seasons is shown below:

FIGURE 4

The Seasons of Excavations at KHD

THE WADI TUMILAT, EASTERN NILE DELTA

The Wadi Tumilat was originally one of the Nile distributaries, running between the apex of the Delta and Lake Timsah (one of the Great Bitter Lakes and today part of the Suez Canal). Later during Pharaonic times, two artificial canals were built to facilitate water travel from the Nile to the Red Sea – the first was the smaller northern canal built during the reign of Senusret or Ramesses II, the larger southern canal was not dug until the reign of Nekau II. During the dynastic period (Old Kingdom to Late Period), the area was part of the VIIIth Lower Egyptian nome, whose capital was Tell el-Maskhuta (no. 58 – tentatively identified as Pithom).

Two large-scale archaeological surveys in the Wadi Tumilat have give valuable insights into the occupations patterns of the area: in the 1920s an Austrian mission carried out a walking survey between modern el-Abbasa (western entrance of the wadi) and modern Ismailia (Schott et al in: MDAIK 1932) while in the late 1970s and early 1980s a Canadian mission carried out an extensive survey in the entire Wadi Tumilat (Holladay & Redmount et al forthcoming).

Based on the survey results of the Canadian mission, there seem to be two main periods of occupation in the Wadi Tumilat - the Hyksos period (Second Intermediate Period – Middle Bronze Age) and the Late Period to Graeco-Roman times (Early Iron Age). However, the wadi has been occupied from the Palaeolithic Period to the present day and further archaeological investigations are needed to build help illuminate the full spatio-temporal settlement pattern.

PREDYNASTIC TO EARLY DYNASTIC SETTLEMENT PATTERNING

Although the Wadi Tumilat is excellently situated as a trade route between the Nile Delta and the Sinai – Southern Levant, to date this cannot be confirmed for the early periods, as few imported objects (from the Southern Levant) have been found within the cemetery of KHD and no evidence is available from the other sites with Predynastic and/or Early Dynastic remains. However, this area is potentially an important southern East Delta trade route, although no evidence like the material found at sites (nos. 31, 47, 48, 53) along the northern route (Ways of Horus-land route from the northern East Delta along the north coast of the Sinai to the Southern Levant) has yet been discovered.

Several large multi-period tells are spaced along the wadi: Abbasa – Tell Shagafiya – Tell el-Retaba – Tell Maskhuta – Tell al-Ahmar (Redmount in: NARCE 1986: 20). These sites seem to be major settlements within the local settlement pattern. Most of these major sites show minimal early occupation - a small percentage of the total objects found scattered on the surface during the Canadian Wadi Tumilat Survey. However, there are certain limitations in using fieldwalking to evaluate a tell, particularly when surveying for the earlier phases. Studies have shown that surface collections of sherds on mound sites are significantly biased in favour of the later periods, by as much as 10 to 1. This is not only as a result of stratigraphic replacement, but also due to erosion of earlier materials. This bias in favour of the later periods is also true of off-mound sherd distribution. The underrepresentation of the earlier periods and overrepresentation of the later periods can be slightly mitigated by scraping the surface by 5 cm to collect potsherds. However, the Predynastic, Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom sherds will only be expected if the level of these occupations is less than 5 m from the surface. Therefore, when conducting fieldwalking to try interpreting site signature, it is essential that it is complemented by exploratory excavation techniques, otherwise the site cannot be assessed for its full archaeological potential, especially the site stratigraphy.

Around these possible early major sites, other sites have been encountered; Tell Samud and Shagafiya, both situated near to Tell er-Rataba, which due to its location in the middle of the Wadi Tumilat and the substantial early occupation, must have been one of, if not the most important settlement in the local settlement pattern.

KHD does not seem to be located near to one of these major sites, rather it seems to be right in the middle between Tell Shagafiya and Tell er-Rataba. Research carried out by J. van Wetering and G. Tassie has compared KHD to known cemetery sites in the East Delta (primarily Minshat Abu Omar and Tell Ibrahim Awad). This research indicated a low ranking for KHD compared to other East Delta cemetery sites. However, the ranking of KHD within the local settlement pattern in the Wadi Tumilat cannot be fully assessed as it is the only late Predynastic to Early Dynastic site so far fully excavated in the region.

By Hassan, Tassie & van Wetering

Registered Charity No. 1142484

Website Design by Callum Johnstone & Lisa De Young Triemstra

Website Maintenance by Lisa De Young Triemstra

Site Content by Prof Fekri A Hassan, Dr Geoffrey J. Tassie & Dr Lawrence S. Owens

(unless otherwise noted)

Copyright © 2025 Egyptian Cultural Heritage Organisation - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.