KAFR HASSAN DAWOOD 2019

KHD Research Project 2019

The KHD Research Project was initiated in 2018 by Dr Geoffrey Tassie and Dr Lawrence Owens as a joint project with Ministry of Antiquities (MoA, now Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, MoTA) to be co-directed by Dr Lawrence Owens (University of Winchester) and Dr Rizq Diab (MoA/MoTA), with Dr Geoffrey Tassie as the project Deputy Director. Regrettably, Dr Tassie died suddenly in 2019 before the first season of the joint project took place. This joint project set in place an ambitious new programme of research to build upon the findings from the 1995-1999 seasons, to include mapping the extent of the cemetery, establishing its connection with the nearby settlement, examination of temporal trends in the cemetery's development, and an examination of biological and cultural change between the Late Predynastic to Early Dynastic periods.

The 'big picture' is to understand how society changed - if at all - when Egypt was unified by King Narmer in around 3150 BC, and the impact of the newly centralised administration at Memphis upon villages, towns, and people. We are also interested in how the site was used in later periods, notably by Late Period, Ptolemaic and Roman populations who buried both humans and animals here three thousand years later.

The 2019 season consisted of an exploratory programme with a small, core team to assess the archaeological area, and to consider what would be possible for our longer term research. We mapped in and opened up a series of 10 x 10m squares in the northern part of the western cemetery, near to the original excavation centre and abutting the edge of the historical Islamic cemetery. Workers from the nearby village, together with specialist archaeologists from Quft, cleared back several feet of sterile sand, before arriving at the ancient flood plain, a much muddier, darker horizon (caused by repeated Nile inundations) upon which the original inhabitants of KHD made their home. The ancient village is also nearby, but little is known about it at present, and it will be subject to future investigations.

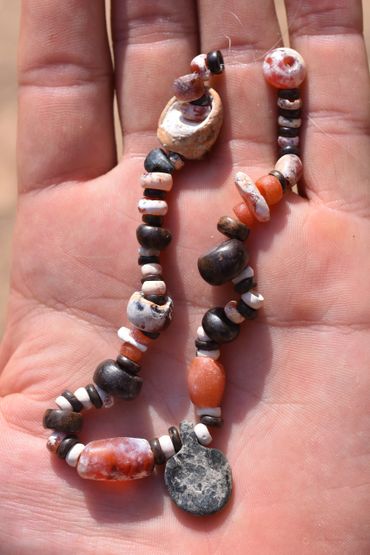

In the 2019 season, we located a series of graves containing human remains and cultural artefacts. The dates are yet to be confirmed but all individuals seem to have been interred between about 3300 and 3000 BC. Most burials contained ceramic vessels, and some also contained offerings such as red, black and white stone beads that - judging from their positions in the graves - were probably necklaces and bracelets. The range of grave goods was not as extensive as the 1995-1999 seasons, suggesting internal differentiation – perhaps based upon status, or chronological phase – within the cemetery.

These were typically single interments, but several contained multiple individuals. What this means is uncertain – it may indicate familial ties, although the reuse of graves may reflect some form of social hierarchy or affinities. As with most burials dating from the Neolithic to the Early Dynastic period, the bodies were interred in a flexed or 'foetal' position, in oval, rectangular or circular graves: this accords with most of the human remains recovered from 1995-1999. Most individuals were buried with their heads facing towards the North, and their faces towards the East, although the presence of other variations may relate to the beliefs of the various groups within the KHD community.

Children were under-represented in the sample, as were males; while this may purely reflect the choice of trench location, it also seems possible that different ages and sexes received different treatment, and perhaps burial locale. The average adult age at death was in young adulthood - only two of the individuals recovered seemed older than 50 years of age. People were largely healthy insofar as we can see from bones; there were some slight markers of childhood stress, suggesting some form of hardship (such as illness or starvation) during development. It is early days, but the cemetery has revealed a great deal of information already – more than we could have expected after a first season. While preservation is often less than perfect, enough remains to assess the population’s possible biological origin, as well as factors such as diet, activity levels and behaviour. The ceramologists and small finds specialists also have a great deal to work with, plotting artefact origin and function, and relating these to the individuals in the graves. We also have all the data from previous seasons to collate and combine with the 2019 findings, and once we have that it will make this the largest and best understood Predynastic cemetery site in the Delta area.

We can then use this formidable dataset to address the bigger questions: what were women's status or roles? Did they change through time? Who wielded power - locals or incomers? Did the village change over time? Did people get ill more or less often? Was this to do with diet or other factors? Did people die younger or older? Were childhoods more or less healthy? We can then compare our findings with funerary evidence from Lower and Upper Egypt, to contribute to the wider understanding of local/regional/supraregional health-related developments. All of these are important issues to be considered within research into the dynamics of the origins of the state.

As with all scientific enquiries, these initial investigations have led to many new questions.

We will keep you updated, so do visit the website again!

KHD 2019 Gallery

Registered Charity No. 1142484

Website Design by Callum Johnstone & Lisa De Young Triemstra

Website Maintenance by Lisa De Young Triemstra

Site Content by Prof Fekri A Hassan, Dr Geoffrey J. Tassie & Dr Lawrence S. Owens

(unless otherwise noted)

Copyright © 2025 Egyptian Cultural Heritage Organisation - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.