Kafr Hassan Dawood 95-99

1995 Season

Our main aims were to examine the human remains in the huge Western cemetery, and to explore the enigmatic area in the East of the site that contained an unusual find: a cow and child burial.

We opened up a series of squares in the western section, and found 27 graves (19 of which contained human remains), which spanned the Predynastic/Early Dynastic period to the Ptolemaic. The early graves were simple burials, the bodies having been tightly flexed on their left sides, looking towards the east, and accompanied by everyday objects. However, three large, mud-filled graves were also found, containing numerous wine jars – some marked with the makers mark – beer jars alabaster vases and slate plates.

The cow and child burial turned out to be an intrusive interment (dating to the Ptolemaic Period), while further investigation in the area uncovered a ring of cow burials, all surrounding child burials in the centre; this unusual series of interments dated to the Late period. A scatter of Late Period to Ptolemaic adult burials were also found in this area, along with – more unusually – goat burials dating to around the same period.

1996 Survey Season

The excavation season was accompanied by a full survey of the site and surrounding area. Led by Prof. Paul Sinclair and Dr. Mohammed Abdel-Rahman under the directorship of Prof. Fekri A. Hassan, the aims were to create a topographic map of the site, lay out a site grid and datum (with the total station), drill core the site to establish the microstratigraphy, and to carry out a subsurface survey of the Western Cemetery using GPR, resistivity and magnetometry.

Although the GPR did not work as well as hoped owing to the nature of the sediments, we achieved excellent results from the magnetometry and resistivity, which identified key geological variations and archaeological remains. The results of this geophysical prospecting were tested in the excavation season, and proved very accurate in their identification of archaeological features.

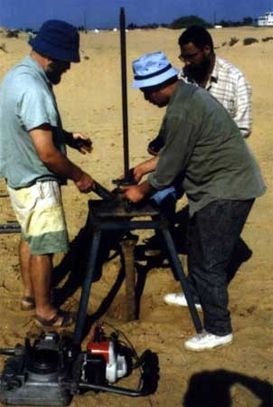

The coring programme used a BORRO motorised augur with a 50 mm bore, which was used down to seven metres; the cores were extracted using a hand lifter capable of exerting 12 tons of pull. In addition to overlying aeolian sand, we identified five main units (in younger to older order) as follows: 5) Alluvial-Colluvial Unit, 4) Upper Nile Mud Unit, 3) Upper Sand Unit, 2) Lower Nile Mud Unit, 1) Basal Sand Unit. The full results of this analysis can be found in our bibliography.

Figure 11.

Prof Paul Sinclair (left) with Dr. Mohammed Abdel-Rahmen Hamden and Dr. Mohammed Ibrahim Hamdi Hafez operating the motorised drill corer.

1996 Excavation Season

We returned to KHD in 1996, in the baking heat of a July season! By now we had the measure of the site, and had developed a recording system that would standardise and clarify this complicated site and the relationships between the various areas and strata. We had a lot of plans for the season, namely to excavate and record the southern part of the Western Cemetery, analyse the ceramics and other artefacts, and – most importantly – to train a group of Egyptian and international students in our methods, in order that future seasons (starting in Spring 1998) would go without a hitch.

Forty-one graves were excavated, about half of which were Predynastic to the very early years of the Dynastic Era, and the others from the Late to Ptolemaic Periods. We were particularly interested in the earlier burials, as they would be able to help us address some of our research aims, such as understanding the human impact of Egyptian unification around 3000 BC, and the nature of trade between this area, Upper Egypt and Canaan. People’s health, sex, age and the items buried with them were all considered, along with their diet and how this did (or didn’t) change in the very early years of the unified state.

The burials were ‘typically’ predynastic – the bodies were interred in oval pits and curled up in a flexed position (as if they were asleep), usually on their left sides and looking towards the east. Other variants included compact mud-lined graves, one of which contained a slate bowl, numerous calcite vessels, and a variety of fine and coarse wares. However, the most remarkable find was the large Early Dynastic mud-filled tomb (970). Although it has been cut by three later (Late/Ptolemaic Period) graves, enough remained to bear comparison with another tomb (913) excavated in 1994/5, and which had contained a pottery jar bearing Narmer’s serekh. The structure suggests that this subterranean tomb once bore a shrine on the eastern side, with a mud ramp rising from the south. An enigmatic linear feature was found nearby, comprising grey sand and gravel with assorted fish bones and teeth and freshwater mollusc remains. We suspect that this area was a mortuary complex in the Early Dynastic period, predating the development of similar – yet more monumental – complexes at Giza and Saqqara. We do not yet know what happened to the site through time, but the Nile is known to have deposited around 10cm of alluvial deposits per century in this area, so that this 5000 year-old site now lies five metres below the current ground level.

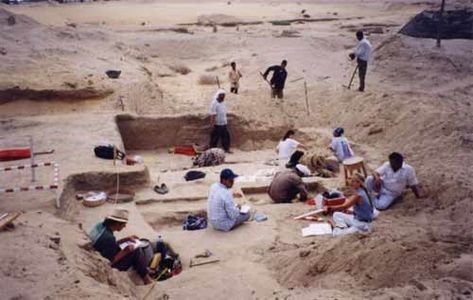

Figure 12.

General view of the southern trenches in with G. J. Tassie and Bram Calcoen in the foreground.

Figure 13.

Dr, Mohammed Abdul-Rahman Hamden and G. J. Tassie discussing the planning of

Grave 970

Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Maybeline Gormley and Prof. Simon Hillson excavating the pottery coffin in Grave 962

1998 Season

Our 1998 season ran from April to May (so wasn’t as hot!) and continued with the aims of previous seasons, along with the analysis of the large monumental tomb (970) identified in 1996, to investigate the associated aeolian sand and gravel feature, to extend the excavation towards the north and to continue with the recording of finds data and the training of students.

Fourteen new graves were excavated, while three exposed in 1997 were recorded and the finds recovered. One (974) was mud-filled, and contained hundreds of beer jar fragments, Egyptian alabaster sherds and a broken sandstone quern. Child burial 998 contained a Wadjet-eye amulet, while the largest grave (970) occupied us for much of the season. The three chambers cutting through the tomb (970) were confirmed to be Ptolemaic graves 1000, 1006 and 1013. The original tomb was oriented N-S and measured 6 x 4 metres, and contained a large cache of beer jars, wine jars and a large, lidded storage jar with stand. Many of these vessels were inscribed with pot marks. We also recovered a cache of stone vessels – including alabaster vases and slate bowls – although the presence of a robber trench in the west-central past of the tomb indicated that the body has been located and looted. The only remains of the funerary regalia included some slate beads and bracelets, stone vessel sherds and a large pot stand. Other finds included a stack of five bowls and five plates (with associated animal remains) and a pressure-flaked flint knife.

Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Excavation of Grave 970

Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Excavation of Square 105 in the northern part of the

Western Cemetery.

1998-1999 Field Season

The 1998/1999 season was the fifth at the site, and continued the work of previous campaigns. We also aimed to map the extent of the Predynastic cemetery, to finish the drawing and recording of artefacts from the graves, to complete the excavation and analysis of skeletal remains, and to carry out a full analysis of the ceramics in collaboration with students from Egypt and overseas.

Forty-three graves were excavated, of which 25 were Predynastic and 18 Late Period or Ptolemaic. Condition of the remains was very poor owing to the high water table in the area, and only 14/25 Predynastic graves contained any skeletal remains. The later burials were all located to the southern part of the site, while the Predynastic remains – including a burial inside a ceramic coffin – were largely towards the north. The mapping of a large palaeo-channel running through the site indicated that it had preceded the Predynastic cemetery by perhaps as much as 2000 years. Locating the burials near this channel may have had some significance, as six of the interments were very well-equipped and probably reflect some social hierarchy at the site. Highlights included semi-precious stone beads, faience, an inlaid make-up palette (with traces of gold), copper chisels/needles, and numerous vases and plates (some with potmarks). Unusually, disarticulated burials with multiple loose skulls were found, overlying intact primary burials in the same grave, while at least one grave contained a male, a female and a child (1027).

Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Pottery coffin found in Grave 1025 situated in the

southern part of the Western Cemetery.

Figure 18.

Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Geoffrey Tassie and Richard Lee excavating grave 1041

assisted by Serena and local girls.

1999 Survey, Research & Excavation Season

The sixth season at the site ran from August to October 1999. Both excavation/research and survey components were carried out.

The archaeologists continued with work already started at the site. In addition, they focused on a very large grave (913) that had initially been located in 1995. In accordance with the SCA’s wishes the grave and all of its contents had been exposed so that they could be preserved in situ as part of a large open-air museum. A brick structure was built over the remains in order to protect it from the elements. The museum idea having since been abandoned, Mr. Hangouri (Canal Zone Director) cleared the artefacts in 1998/9, and the resulting remains were analysed by our team as part of the field season.

Fieldwalking in the W of the site revealed a scatter of Predynastic fragments that are likely to have been thrown up in the development of the modern cemetery; these notably included a pottery coffin. Nothing was found towards the S, although a large depression among the dunes was considered to be the remains of the palaeochannel recorded in 1998. Gezira Hadra (Green Island) was also explored, but no evidence of human habitation was noted. The survey was followed up by consultations with village elders, in order to record their memories of the site and area. Their accounts pinpointed two distinct Islamic cemeteries – each for a different group of villages – and also a Christian cemetery towards the east. They also revealed that a farmer to the south of the site was planning to plant fields right up to the road that marks the boundary between the two areas. Test pitting was also carried out, with little found towards the west or the far north, other than establishing the extent of (and profile of) the ancient floodplain. A pit slightly to the north of excavation area sq. 106 revealed a partial Predynastic burial, and a modern burial immediately adjacent. A further pit revealed the edge of the floodplain and a closely grouped series of Predynastic graves. Further pitting towards the east revealed extensive Predynastic burials, and confirmed our earlier suspicions about the extent of the modern cemetery. Pitting towards the south hit the ancient floodplain at 1m, along with potsherds, a hearth containing mollusc shells and charcoal, and possibly the remains of a house. This area will be returned to in future excavation seasons.

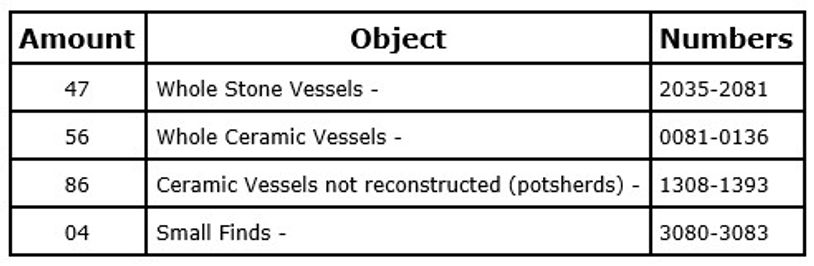

Table of total grave goods examined

Registered Charity No. 1142484

Website Design by Callum Johnstone & Lisa De Young Triemstra

Website Maintenance by Lisa De Young Triemstra

Site Content by Prof Fekri A Hassan, Dr Geoffrey J. Tassie & Dr Lawrence S. Owens

(unless otherwise noted)

Copyright © 2025 Egyptian Cultural Heritage Organisation - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.